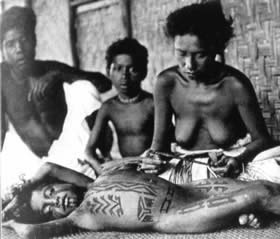

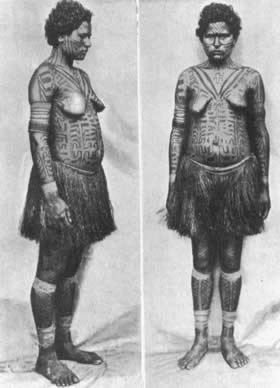

Young Motu girl getting tattooed, ca. 1930.  Waima woman wearing full body tattooing, ca. 1910. Her sternum tattoo below the neck was called "frigate-bird," and the branching elements on her abdomen "centipede." The turtle-shell motif appears on her legs above the knees, and the "fluttering" or "flying spark" motif represents the lines tattooed on the face. The photographer could not provide a detailed record of the tattoo patterns worn beneath the petticoat, although he doctored this and many subsequent photographs by painting over them so they would show more clearly. This was not an uncommon practice in Papua, because tattoo pigments did not show up well on dark complexions. The subject has been posed in front of a white canvas sheet to provide contrast. |

As far back as the old men and women can remember, tattooing has been a tribal custom of the coastal peoples of Papua New Guinea. Among the Motu, Waima, Aroma, Hula, Mekeo, Mailu and other related southwestern groups, women were heavily tattooed from head to toe, while men displayed chest markings related to their exploits in the headhunt. By World War II, however, tattooing traditions largely disappeared in these areas and today only the Maisin and a few neighboring peoples of Collingwood Bay in southeastern Papua remain as the last coastal people to continue tattooing itself.

Tattoos were generally inked upon women in a fixed order among all coastal Papuans. First, girls between five and seven years of age were tattooed on the backs of hands to the elbows and from the elbows to the shoulders. Girls between seven and eight were tattooed on the face and lower abdomen, the vulva and up to the navel, then the waist down to the knees and the outside of the thighs. At ten, the armpits and areas extending to the nipples were tattooed with the throat done shortly thereafter. When puberty approached, the back from the shoulders down, then the buttocks, back of the thighs and legs were marked. When ready for marriage, V-shaped designs from the neck down to the navel were tattooed. Sometimes, special tattoos could be added if the father, brother, or close relative of the girl killed another man, or if they showed prowess in fishing or trading expeditions. All of these markings were ritualistic, and in some cases erotic. If a girl did not have them, she was not acceptable for marriage.

Many of the tattoo motifs were passed down through the family - from mother to daughter, and sometimes from father to son. Unfortunately, ethnographic information on most tattoo motifs has been lost - modernity and missionization are largely to blame. For example, tattoos related to the headhunt have been largely forgotten, since killing was outlawed in 1888 when Great Britain annexed Papua. Tattoos associated with the Hula and Motu trading voyages (lakatois) are also no longer seen; motorboats have replaced the traditional sailing vessels and these once formidable expeditions are no longer dangerous. Moreover, missionaries began discouraging initiation ceremonies in the early 20th century, and today tattoos are no longer needed for marriage. Thus, the meaning of Papuan tattoos is fading and gradually being forgotten.

Tattooing Kits and the Women Who Used Them

Typical tattooing kits were fairly simple and the technique employed to apply the tattoos was a form of hand-tapping. Among the Motu, the wooden "hammer" was called iboki and the needle-like gini was a lemon branch twig with a thorn projecting out at one end. The Motu first painted the desired tattoo motif on the skin and allowed it to dry. With the gini held in the left hand, with the point of the thorn almost touching the skin, and the iboki held in the right hand by the small end, the gini was tapped with enough force to cause the thorn to pierce the skin. For finishing the tattoo, the gini may have had three or four thorns tied together for filling.

Usually, tattoo pigment came from the charred remains of the candlenut. Candlenut (Aleurites moluccana) was also utilized as pigment in Hawaii (kukui) and other Pacific islands in Polynesia. Interestingly, I have found that the leaves and sap of the candlenut tree were used throughout Polynesia, the Philippines, China and Indonesia in the treatment of arthritic joints or as a healing application for chapped lips, cold sores and sunburn. Even in Papua, the Sinaugolo tribe specifically utilized several types of "medicinal" tattoos to treat rheumatoid arthritis. These marks were usually grouped around aching joints on the back, neck, shoulders, and forehead. Triangular motifs seen under the left breast of a Sinaugolo man in the 1880s appeared to one explorer as "hav[ing] been tattooed for palpitations or uneasy sensations in the region of the heart."

Traditionally, tattoo artists were almost always female and different women were employed for tattooing specific parts of the body. Among the Mailu, facial tattoo artists seem to have been paid more, as this work was the most painful and dangerous. Around 1900, a typical payment for facial work included two strings (pairs) of armshells, quantities of cockatoo and parrot feathers and a string bag, whereas other parts of the body may have only brought small payments of cooked food.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Twitter

Twitter

09.22

09.22

Set-bisnis

Set-bisnis

0 komentar:

Posting Komentar